A highlight of the week on Twitter has been the hashtag from @bruceholsinger #thanksfortyping which reveals the contributions of anonymous wives to the research of male academics:

A peek at an archive of women’s academic labor: wives thanked for typing their husbands’ manuscripts. 1/5 #ThanksForTyping @TheMedievalDrK pic.twitter.com/yAf03lsweg

— Bruce Holsinger (@bruceholsinger) March 25, 2017

This one is AMAZING. “My wife” did his paleography for him: transcribed, edited, and corrected from 16th-c. editions. #ThanksForTyping pic.twitter.com/w0Lk0knfDa

— Bruce Holsinger (@bruceholsinger) March 26, 2017

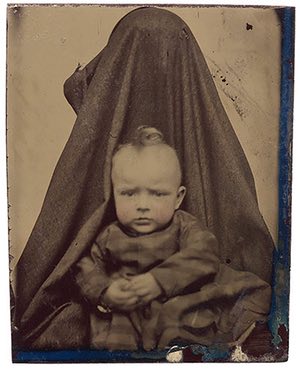

The entire thread is well worth reading (and there are also some more recent positive examples where wives are named and acknowledged). It reminded me of the uncomfortable images of hidden mothers in Victorian photographs:

In a previous post, I provided some links on the disproportionate load of care work, emotional labour, housework and service that women carry in and out of the academy. #Thanksfortyping shows how academia has relied on this work.

Last year I read Annabel Crabb’s (2014) The Wife Drought:

For many modern mothers, progress at work means the privilege of working herself into the ground in two places rather than one.

It reads as though written in a rush (presumably the author was busy doing wifely and motherly things, as well as working as a political journalist and television show host), but its point is an important one. Subtitled Why women need wives, and men need lives, it reveals that some jobs are designed to function best with the presence of ‘a wife’ – that is, a person who does “the unpaid work that accumulates around the home” – and both women and men lose out as a result. Similarly in Overwhelmed (2014), the ideal worker – the person who arrives first in the morning, leaves last at night, is always ready to travel, and never turns off work even on vacation – is revealed as a myth that persists because it just might describe the (usually male) boss.

Undoubtedly, academics can work more (and research and travel in particular) if someone else cooks, cleans and shops; arranges childcare and looks after sick children; takes control of the administration of everyday life; and acts as a research assistant on the side. In a scholarly context, Hey and Bradford (2004) and Thornton (2013) write eloquently about this ideal (masculine) academic subject. (An aside: dystopias can be defined as places that, among other things, try to mould people into an ideal).

#Thanksfortyping and those hidden mothers shock because, while acknowledging their presence, the nameless and faceless women lack any autonomy or subjectivity. Times have changed, but the pressures of invisible work remain. The recent viral video of the interrupted BBC interview nicely revealed a glimpse behind the scenes, and prompted a spoof interview with a mother.

Work/life balance has been proposed as a solution but life is far more complex than that slash symbol suggests, as Toffoletti and Starr (2016) demonstrate in an excellent article:

[Women academics see work–life balance] as something they are expected to personally manage; an impossible task; detrimental to their careers; and as a topic that remains unmentionable at work … [Work-life balance creates] additional burdens for academic women to personally and successfully manage multiple work demands within and beyond the domestic sphere … The concept of work–life balance rests on a highly problematic set of assumptions about work as … distinct from life … [I]n attempting to create a university environment where the issue of work–life balance is rendered visible and important via policy schemes, paradoxically, women academics respond to such schemes by evoking a language of pressure, failure and opting-out…

It’s difficult to conclude this post neatly. Where to from here? While I want to advance slow academia as a solution, this risks over-promising on a fledgling and complex endeavour to change practices in academia. For a quicker fix, perhaps we should shift exploitative labour to fem-bots?

I think this can also apply to some (emphasis on ‘some’) of the ‘high achieving’ women in academia. Along the way I have meet some woman academics (high achieving according to the ladder of progression) who have stay-at-home husbands that have given up career for the wives to pursue their academic dream. It troubles me because of how such women position the rest of us who just don’t happen to be able to achieve that promotion to that next level in academia because we fail to show the necessary ‘evidence’ that equates to many hours of work outside of regular working hours along with a speed of work that drives you to insanity.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Good point, Linda. Crabb uses the term ‘wife’ to designate wifework done by men and women. Historically, careers like academia do assume someone other than the academic does this work. I still remember an interview with Denise Bradley (VC of UniSA who had 4 children as a single mother) saying that when she started working in the university system women didn’t get superannuation!

LikeLike

Reblogged this on feminist academic collective.

LikeLike

Pingback: Reading and wondering | The Slow Academic